The Untold Story of Ethiopians in Cuba

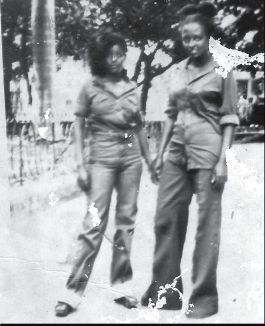

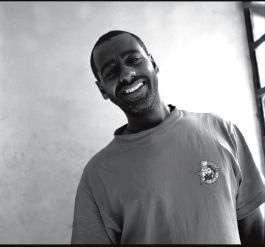

Aida Muluneh (Courtesy photo)

Aida Muluneh (Courtesy photo)

Tadias Magazine

By Tadias Staff

By Tadias Staff

Updated: Sunday, August 10, 2008

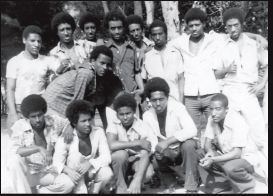

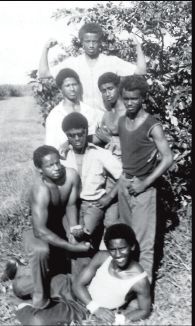

New York (Tadias) – In 1979, under Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile-Mariam, the Ethiopian government sent thousands of Ethiopian children to Cuba to be educated. Cuba, an ally of Ethiopia in the Ethio-Somali war, offered housing and education for war orphans. The Cuban government accepted 2,400 Ethiopian students, aged seven to fourteen, to study at Escuelas Secundarias Basicas en el Campo (basic rural secondary schools) – on the small island of Isla de la Juventud.

The following is an interview from our archive with photographer Aida Muluneh, who is filming a documentary about their lives in Cuba.

Tadias: How did you become interested in the “Ethio-Cuban” story?

Aida: I went to a group photo exhibit in Havana in 2003 and prior to my trip I had heard about the Ethiopian students in Cuba. After searching for them, I finally met around 30 students who had been in Cuba for over twenty years. It was an amazing experience meeting these fellow Ethiopians. I soon realized that I had to come back. So in 2004, I went back and begun interviewing them to start telling their story and also to help them get out of Cuba.

Tadias: Why haven’t they left Cuba? And why haven’t they returned to Ethiopia?

Aida: They have had the opportunity to leave Cuba and return to Ethiopia; however they have no means of supporting themselves in a country they left twenty years ago. There is no incentive for them to go back to Ethiopia and resettle because life would be just as difficult, if not worse in Ethiopia. As for other countries i.e. Europe or North America, the remaining student just recently qualified for their UN refugee number. This basically means that they can get in line for a chance to immigrate to those countries.

Tadias: This was a coordinated effort between the Cuban and Ethiopian governments. What efforts did Cuba make to help Ethiopian immigrants adjust to Cuba?

Aida: The Cuban government has been extremely supportive within their means from day one. Even prior to the students arriving, Cuba played an instrumental role in helping Ethiopia during the Ethio-Somlia war. Therefore, upon the student’s arrival, the children were given the basic necessities in order to become acquainted with life in Cuba. One thing that needs to be put into perspective is that as a young child, it is difficult to adjust to any place that is foreign, especially when one is so far away from home. The Ethiopians expressed to me that as children they had missed their country more then anything and I believe this yearning to return is what made it extremely difficult for many. The Cubans have gone above and beyond in providing support to the Ethiopians to this day.

Tadias: Although The Unhealing Wound focuses on those Ethio-Cubans still in Cuba, we understand there have been a number who have managed to leave Cuba and live elsewhere. When did they leave and where do they live now?

Aida: In addition to providing primary education, the Cubans have also educated University students during this time period. For many of the Ethiopian students who attended universities in Cuba they have managed to return back to Ethiopia and find viable means of supporting themselves. In fact during the Derg period, many of the students that completed their education were given housing and job opportunities upon their return to Ethiopia. However, after the fall of the Derg government, many of the students felt that returning back to Ethiopia would lead to further economic hardship. In 1991, the Soviet Block fell and many of the students begun leaving to countries such as Spain, Greece, Holland, U.S., etc. I am not exactly sure how many returned to Ethiopia and how many went to other destinations. My assumption is that the greatest number of Ethiopian-Cubans are in Spain.

Tadias: Is there a network of Ethio-Cubans abroad that help others still in Cuba to immigrate to other countries?

Aida: As far as I know, there is no organized effort by Ethio-Cubans that continuously assists the Ethiopians to leave Cuba and resettle to a third country. Although it is a tightly knit community in Cuba, once abroad, it’s more so through the efforts of individuals helping new comers than an established network.

Tadias: What kind of relationship do Ethio-Cubans have with Cuba? Do they identify in any way as Cubans?

Aida: From my observation of the Ethio-Cubans, there is a special relationship between the Cubans and these Ethiopians. It is clear that they still identify themselves as Ethiopians but they have fully taken on Cuban mannerisms and cultural habits in the ways they interact with others and express themselves.

Tadias: You mentioned that many Ethio-Cubans faced challenges in adjusting to their new environment when they moved to Cuba. What were some of those challenges?

Aida: The challenges were similar as any immigrant faces when they arrive to a new country, but imagine that through the eyes of a ten year old. The first problem that they had was the climate. The temperature was a big issue. They were moving from the highlands of Ethiopia to a tropical island. The second was the food. The food in Cuba consisted of pork, rice and beans in contrast to eatingInjera their whole life. Then, of course, language and homesickness were major issues.

Tadias: You left Ethiopia as a child as well. Is there a relationship between your interest in the Ethiopian students in Cuba and your own experience?

Aida: There was definitely a relationship to my life. I went to boarding school at a young age in Cyprus away from my family. One of the things that attracted me to the whole story and enabled me to empathize with them was the struggle I faced as a child who felt alone in a foreign land.

Tadias: Does the Ethio-Cuban story fit into the themes that you address in your photography work?

Aida: My beginning as an artist is in photojournalism and this story at first was supposed to be a series of photographs about these Ethiopians. However, I decided that their story was too compelling to be told solely in still photography. The Unhealing Wound is an exploration of themes that captivate me as a photographer and a filmmaker. It all comes down to capturing life and in this case it is capturing our past history and also documenting the history as it is happening. I hope that thirty years from now, anyone can look back at this film and have a better understanding of our struggles, triumphs and sacrifices as Ethiopians in the landscape of the immigrant life.

—-

Find out more about the film at pastforwardfilms.com.

Find out more about the film at pastforwardfilms.com.